Eliel Saarinen’s wife, Loja (Loy-a) was trained as a sculptor, photographer and model builder. She became a textile designer and weaver when Saarinen became the chief architect of the Cranbrook campus located in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. The campus consists of Cranbrook Schools, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Cranbrook Art Museum, Cranbrook Institute of Science and Cranbrook House and Gardens.

Studio Loja Saarinen was established to design and weave textiles, carpets, and rugs on a commission basis for many of the Eliel Saarinen designed buildings on the Cranbrook Campus. Consequently, Loja became the director of the weaving department at Cranbrook from 1929 until her retirement in 1942. At full production, Studio Loja Saarinen held close to 30 hand looms.

Eliel Saarinen began designing his house at Cranbrook in 1928, and he and Loja moved into the completed home in fall 1930. They lived in the house until Eliel’s death in 1950.

In 1942, when Loja Saarinen retired from Cranbrook, Strengell replaced her as head of the Department of Weaving and Textile Design.

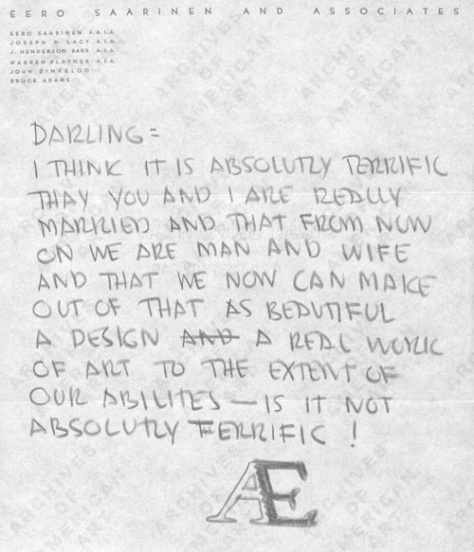

Aline was the associate art editor and critic for the New York Times and recently divorced when she met Eero in 1953. She was on a trip to Detroit to meet the young architect whose General Motors Technical Center had proved to be a great success. She was to write a profile of Saarinen for the New York Times Magazine, eventually published with the title Now Saarinen the Son authored by Aline B. Louchheim. She would become Aline B. Saarinen a little over a year later.

A look into the intimate correspondence between both Eero Saarinen and Aline Saarinen is available online, digitized by the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian as the Aline and Eero Saarinen Papers, 1906-1977. Their letters track the history of their romance and provide an inside look at how two stars in their respective fields came to be partners.

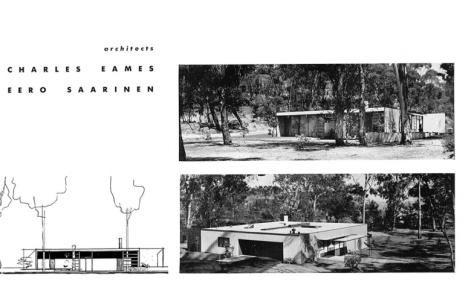

After their marriage, Aline relocated to Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where she continued to work as associate art critic for The New York Times and where she served as Director of Information Service in the office of Eero Saarinen and Associates (from 1954 to 1963). They had a son and named him Eames after Eero’s long time friend Charles Eames.

After Eero’s sudden death in 1961, she and Saarinen’s longtime partners Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo traveled around the country, making sure the firm’s nine commissions under construction or in design (including the TWA Terminal, Dulles Airport, two residential colleges for Yale, the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the CBS Building) were all completed as Saarinen buildings. In 1962, she published a book of his writings, including black-and-white photographs of his projects, Eero Saarinen on His Work. This book is currently on display at KMAC as part of the Eero Saarinen A Reputation for Innovation exhibit.